- Home

- David Layton

The Dictator Page 7

The Dictator Read online

Page 7

THEIR FIRST STEP on their journey to freedom was Lisbon, a city awash with refugees like them. The agency responsible for transporting them to their new life in the Dominican Republic put them up in a small hotel. Felix, who at twenty-one was five years older than Karl, had taken the one single bed in their room. Karl slept on one of the three cots. It was crowded, but they were grateful to have any sort of room at all. The agency had also given them a stipend to purchase clothes and food.

But before they left on the next step of their journey on the Nea Hellas, a ship that awaited them in the harbour, Felix decided that Karl was going to lose his virginity.

“Let’s put our stipend to a more interesting use” was how he put it.

Though Karl was fairly certain the agency money was not meant to be spent on prostitutes, he was happy to go along with Felix’s instructions.

“We can’t have you travelling to the New World as a virgin,” declared Felix. “You can take the clap with you as a souvenir.”

The Polish woman in the brothel Felix found for them was pretty in a practical and practised way, and the whole event was over before he knew what to make of it. He’d felt more exhilarated afterwards, when Felix and the other men with whom they shared the hotel gave him congratulatory pats on the back, but after he slipped into his cot, no longer a child but a man, he thought he’d never felt lonelier. Everything he had done up until that point had been directed toward his own survival, but the night in the brothel was different. It had been an act of pleasure, and so in a sense, even before watching Lisbon and Europe disappear behind the wake of the Nea Hellas, he’d taken his last step from family and home.

The ship was headed for New York. Many on board were, like Karl, refugees leaving behind one world for another—men who’d fought in the Spanish civil war, French politicians, Polish army veterans—but there were also men on business and even, to Karl’s surprise, a few tourists returning home. During the passage across the Atlantic, they were all designated as passengers, served by waiters who wore white gloves and called them Sir.

This sudden equality offered Karl the opportunity to discriminate. On a ship where uniformed men opened doors for him, Karl responded with a polite acceptance that demonstrated neither contempt nor undue deference. His acknowledgement of privilege and responsibility had come from his father, and the farther the ship sailed, the closer to his old self he became. Not everyone was capable of negotiating their way with the same ease and acceptance. Felix either talked too loudly or sank into a sullen silence, and Karl couldn’t help observing that he, along with several other men from Diepoldsau, ate their food with a hint of gluttony—a habit of which Karl silently disapproved.

If you believed Jacob Weinberg, whom Karl had been seated next to for dinner service, this journey heralded new beginnings. Like Karl, Mr. Weinberg, his wife and two children were travelling to the Dominican Republic. With thinning hair and wire-rimmed glasses, Mr. Weinberg looked older than most of the other refugees. More surprisingly, he had a family. Karl had never envisioned parents and children making the trip, and it made him look back at his own family with bitterness. If only my father had had more foresight, we could have been the Weinbergs, he thought.

Perhaps because of his age or because he was a father, Mr. Weinberg seemed to know more than the others about what was happening and why.

“The British don’t want us in Palestine. And we tried to go to America, but they don’t want us either. Only President Trujillo has opened the door to Jews.” Then he said something that truly surprised Karl. “God has interceded on our behalf, and we are going to work the land and remake ourselves.”

Karl had never given God much thought; He just wasn’t something talked about with any seriousness in his household. Except during the High Holidays, when his family attended synagogue, discussions of God weren’t considered in good taste. That was for the poverty-stricken Jews of Leopoldstadt district, many of whom had come to Vienna from Russia and Romania. They dressed in outlandish clothes, smelled, and talked of God and His business seriously. His father always believed they brought with them the bad odour of anti-Semitism. “They’re an embarrassment,” he said. If the Austrians disliked the Jews, he’d heard his father say, it was because of them. They didn’t fit in.

But Mr. Weinberg wasn’t dressed outlandishly—in fact, because he’d managed to bring with him not only his family but many of his possessions from Germany, he was one of the better dressed passengers on the boat, and he didn’t wear a long beard or a kippa. His fourteen-year-old daughter, Ilsa, was blond, like Karl, and spent her dinners offering Karl her shy smiles. It made him wonder why it should be God’s business to bring her, her family and Karl halfway around the world to live in a strange new land together. If it was His business, then why not save Karl’s family too? For that matter, why not just kill the Austrians who’d humbled his father and forced Karl to flee? Or Hitler? That would be a God Karl could believe in.

After the plates had been cleared from their table, Jacob Weinberg turned to Karl and asked, “Are you alone?”

Karl shook his head. “I share a cabin with four other men.”

This wasn’t what Mr. Weinberg was getting at.

“I mean do you have any relatives meeting you when we arrive?”

There was a code among the refugees not to pry into one another’s past. Some couldn’t stop talking, but the silence of those who wished to say little or nothing was respected. Karl, for instance, had never asked after Felix’s past, and Felix had never asked after his.

“No,” Karl answered.

“Come with me,” Mr. Weinberg said, getting up from his seat.

Karl followed him into the ship’s lounge with unforeseen gratitude. He didn’t like it when anyone thought he was in need—one of the reasons he’d been uncomfortable about the other men knowing he was a virgin—because it made him feel weak, and weakness was something he’d seen in his father. It was dangerous. For Karl, pity slid straight into contempt. But Mr. Weinberg was his father’s age, and he’d made it onto the boat. Karl felt neither pity nor contempt for him.

The large wooden door with a metal studded porthole was open, because the evening was warm, the sea calm. So far it had been a good crossing, thought Karl, who’d grown up with tales of great sea disasters, where ship-wrecked survivors found precarious sanctuary on islands much like the one he was heading for. Yet here was the smell of coffee and beer and pleasant comfort.

A group of refugees had already assembled along a rectangular table whose best seat was reserved for Mr. Weinberg. On the table was a large and detailed atlas.

“This is the Dominican Republic.” Mr. Weinberg motioned Karl to come closer, so that he might better observe the green clump of land on the map that lay open before them. “It’s a very large island. Notice that there’s another country on the island called Haiti.” Mr. Weinberg traced the rickety boundary line, which looked as if it had been drawn by the unsteady hand of a child, his finger moving north to south, then turning eastward along the Caribbean coast toward the capital. “This is Ciudad Trujillo,” Mr. Weinberg said. “The City of Trujillo.”

One of the men in the group expressed surprise that the president shared the same name as the city. Was it a popular name?

“The president renamed the city after himself,” answered Mr. Weinberg.

This impressed the refugees sitting around the table, including Karl. Mussolini hadn’t renamed Rome after himself. Even Hitler wouldn’t dare change the name of Berlin or Vienna.

“What sort of man names the capital city after himself?” someone at the table asked.

“A dictator,” answered another.

“What does he want with us?”

The refugees were more than curious; they were becoming suspicious. Who was this man with the power to save their lives? And why should he do that? Weren’t they all Jews? Nobody liked Jews. This was something Karl didn’t need to think about; it was something he just knew. They could be po

or and dirty or rich and clean, it didn’t matter; it was an insight his father never possessed, for all of the obvious hatred that ended up surrounding him. Bernard Kaufmann thought of Jew hatred as some sort of administrative mistake, as if presenting the correct information to the acting authorities could rectify everything.

“He wants our labour,” answered Mr. Weinberg.

“Why? Doesn’t he have enough of it in his own country?”

“He wants us,” reiterated Mr. Weinberg.

“What about those people?” A man pointed to Haiti on the other side of the shaky border line.

“I’ve been reading about all this. It’s a poor but proud country.” Mr. Weinberg turned to Karl as if they were all attending a Passover dinner; it was the youngest at the table who most needed to learn the important questions of the day.

“All the islands you see here in the Caribbean Sea, they were like prisons. Each and every one held slaves. Millions of them, all working for men as cruel and uncaring as any pharaoh of Egypt. The slaves came from Africa, and some tried to become free, but only in Haiti did they succeed. They killed their French overlords and proclaimed themselves the first black republic in history.”

Karl and the rest of them all stared at this strange land populated by free slaves, its blue and red flag embossed with an insignia of two cannons, a fan of spears and a lone palm tree.

“So they’re black?” asked someone at the table.

“Yes,” said Mr. Weinberg.

“Then what about the Dominicans?”

“They’re Spanish.”

“So they’re not black?”

“They’re brown, I think.”

Mr. Weinberg shifted his finger back up to the north coast as if to move the conversation forward. “This is Puerto Plata, which in Spanish means ‘port of silver.’ It was from here the Spaniards transported their gold and silver and precious stones. It was here that Christopher Columbus first discovered the New World, it was here that European civilization first took hold, and it is here”—Mr. Weinberg stabbed at an empty, nameless patch of land just east of the silver port—“where we’ll be settling.”

Farming in the tropics had seemed an impossibility while surrounded by the snow-capped mountains of Switzerland, but it seemed even more so now that they were steaming across the Atlantic on their way toward the tip of Mr. Weinberg’s finger. Everyone had questions to ask: What could they grow on the land? Were there houses for them to live in, or would they need to build their own? Who was already there? And what about diseases? It was the tropics; everyone knew people died in the tropics.

“So blacks on one side, Spaniards on the other, and once again, we’re in the middle.”

The man who said this offered a cautious laugh, which was picked up by all except Mr. Weinberg, who most likely thought it was God who was in the middle of all things. In Karl’s experience, it was men, not God, who had the power to destroy lives or save them. They were sailing toward one such man whose power was so far-reaching he could rename the capital city after himself. Knowing this made Karl feel exposed and wary, as if he were merely cheating authority, not defeating it. For all that he’d heard around the table, he still had no idea what had motivated this man or his country to take in Jews, but he suspected the answer might not be pleasant.

After the meeting ended, a Spaniard who had overheard their conversation leaned next to Karl at the railing. “The Dominican Republic, eh?” The man let out a morose whistle. “You’ll die there for sure.”

But Karl had not come this far, and done what he had done, just to die. And he wouldn’t. That was the promise he made to himself as the boat glided past the Statue of Liberty’s unexpectedly stern and gloomy face. America was the future, but not his. He and the other colonists—for that was what Mr. Weinberg and the others had started to call themselves—had been issued temporary visas for the United States only after they’d been able to prove they were travelling on to the Dominican Republic, that a country other than America was willing to take them in.

The boat docked at Ellis Island, where the officials wore ill-fitting uniforms and looked bored. Some had faces like pigs, fat and red, while others were long and narrow with sallow cheeks. Unlike the Swiss guards, these men could not be bribed or appealed to. They were doing their job, and their job was to keep them on Ellis Island and make sure none of them ever set foot on Manhattan, until another boat was ready to take them away.

And when would that be?

No one knew. Not even Jacob Weinberg, who was taken to another building, one for families, while Karl was moved to an enormous dormitory filled with single men. Again they were refugees, not passengers, barely tolerated and strictly controlled. In this atmosphere, Felix, whom Karl guilty admitted to himself he’d been avoiding during their boat journey, once more came into his own.

“They think we might be fifth columnists.”

Karl looked at him questioningly.

“It means they think we might be German spies, so they won’t let us go to New York, even for an hour. First we are Jews, now we’re Nazis. We are everything to everyone except what we are.”

They were outside when he said this, staring at the skyline, and the high wall of brick and stones, the great tall buildings, seemed menacing even in the sunshine. Cars could be seen speeding along the far shoreline, oblivious to their existence.

“I was in New York,” a woman said, joining them. Her name was Esther, and Karl recognized her from aboard the Nea Hellas. After complaining about the food and service, she’d taken to her cabin and disappeared. It was rumoured that she’d been a talented pianist and was bitter that the Nazis had put an end to her career. “And I’ve been to Boston and San Francisco and Philadelphia.” She named a few more places that Karl recognized from the westerns he’d watched at the Stadtkino cinema back in Vienna, places like Albuquerque, New Orleans and Houston. It seemed incredible to Karl that he was here, in this same land.

“Are you travelling to the Dominican Republic?” she asked.

“Are you?” Karl asked, incredulous. He had no idea what it would be like, but he was certain there weren’t going to be any cabin doors to hide behind.

“Yes.”

“What do you think it will be like?” Karl asked her, because she seemed so well travelled.

“I don’t think it will be anything like this,” put in Felix.

“No, I suppose it won’t,” she said mournfully, staring at the New York skyline that lay just beyond their grasp, along with the road that could take them there.

Eleven days later, they were loaded onto guarded buses and taken along that very same road. Requests were made to drive through the city, if only to take a look, to be treated as a tourist, a visitor. Instead they were taken straight to a dock, where a cargo boat far smaller and less hospitable than the Nea Hellas, with thick rust stains running down its sides, was waiting to take them to Puerto Plata.

6

THE COLONOSCOPY WAS, AS THEY TERMED it, “precautionary”; they were searching for precancerous polyps. But the only thing the monitor revealed, as the camera snaked its way up Aaron’s intestine, was a glistening pathway of healthy tissue.

Afterwards, in the recovery room, he felt his stomach cramp, the body’s price of having been made to reveal itself, and he pulled his knees closer to his chest in the hope of staunching the stabs of pain. He was in a room with other beds, other patients, all recovering beneath dimmed lights and thin blankets. He heard someone moan, and then, as if it were a birdcall, someone else moaned in response.

It had taken another attack after the mall for Aaron to see a doctor, who’d pressed her fingers into his belly, asked a few questions and then booked him for a colonoscopy.

“Is there something wrong?” he asked.

“That’s what we’re going to find out,” the doctor told him.

His wife would have driven him to the hospital, if Aaron had still been married, because that’s what people who were married did for each

other. But Aaron was no longer married, and he couldn’t ask Petra to take him. So he’d locked his father inside the apartment because he’d only be gone for a few hours, made his way alone to the hospital and then up to the fifth floor, where he checked in, disrobed and let himself be wheeled into the OR with a Demerol drip plugged into his forearm.

“You’re free and clear,” the doctor told him after the Demerol wore off, but Aaron knew that he was neither of these things and that what had beleaguered him was a secret polyp, nurtured in some other part of his body, that could be neither found nor excised.

“Why am I having this pain in my gut?” he asked.

“You probably have lactose intolerance.”

“That’s it?”

“You’d like something more? Your body no longer produces the enzyme capable of breaking down lactose, which is found in most dairy products. It’s particularly common among the Chinese and Ashkenazi Jews.”

“You said ‘probably.’ Is there a test?” asked Aaron.

“Sure. Go home and drink a glass of milk.”

Or have some hot chocolate at the mall, thought Aaron.

The sky was startlingly intense as the hospital doors slid open and offered exit. If he didn’t have a wife to drop him off at the hospital, he certainly didn’t have one to pick him up. He’d signed the consent form that demanded he have a responsible adult accompany him home and called an Uber. He reached into his pocket for his sunglasses to cut the brightness but realized he hadn’t brought them with him. Had it been overcast this morning? Aaron couldn’t remember as he stepped into the taxi and slumped into the back seat, the greasy funk rising off the seat-cloth a welcome tonic after the medicinal air of the hospital. As they pulled away, it occurred to Aaron that he’d been tested not only for a missing enzyme in his body but also for proof of patrimony.

His father had always been at such pains to deny him his past, starting the day he’d brought home a census form from school. In a box marked “Religious Affiliation,” Karl had written the word NONE in capital letters.

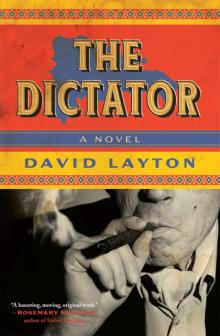

The Dictator

The Dictator